Posted on: 10 April 2025

Hello. My name is Carlyn Boyce, Clinical Lead for the therapy service of the West Yorkshire Staff Mental Health and Wellbeing Hub. This personal blog reflects the content of a training session co-presented with Dr. Kerry Hinsby, Clinical Psychologist.

Avoidable harm in investigations is not inevitable, it is a systemic issue that can be addressed through education, compassionate leadership, and a commitment to intersectionality. In our ‘Employee Investigations – Looking After Your People and the Process’ training, we explored how power and privilege influence investigations, and why a nuanced, intersectional approach is vital.

Avoidable harm in investigations is not inevitable, it is a systemic issue that can be addressed through education, compassionate leadership, and a commitment to intersectionality. In our ‘Employee Investigations – Looking After Your People and the Process’ training, we explored how power and privilege influence investigations, and why a nuanced, intersectional approach is vital.

This work is personal for both me and Kerry - it reflects not just our professional insight but lived experience. As a visibly Brown person and a visibly White person, we co-facilitated this session to emphasise that real change requires collective action.

Why intersectionality matters

Employee investigations in the NHS are essential for ensuring fairness, yet they often reflect broader systemic inequalities. Intersectionality—how overlapping identities like race, gender, disability, and sexual orientation shape experiences—plays a crucial role in determining investigation outcomes. Without acknowledging these complexities, processes can reinforce biases and cause avoidable harm.

The reality of disparities in NHS investigations

Reports like the NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard (2023) and Too Hot to Handle (2024) reveal that ethnically diverse staff face higher rates of bullying, harassment, and discrimination, yet are underrepresented in grievance and disciplinary procedures. This imbalance raises critical questions:

What barriers prevent certain employees from seeking support?

- How can we create equitable investigation processes?

- How can systems identify and dismantle the barriers that prevent people from ethnically diverse backgrounds (in addition: experiencing intersectionality) from accessing support?

Power and privilege: who holds influence?

The Power Cycle, adapted from Sylvia Duckworth’s Wheel of Power/Privilege, illustrates how those closest to the centre -leaders, policymakers - hold the most influence, while those on the margins - women in lower-grade roles, ethnically diverse staff, disabled employees - face greater risk of marginalisation.

In investigations, this plays out in multiple ways:

- Decision-making bias: leaders may unintentionally apply their own cultural lens, reinforcing systemic inequalities.

- Lack of representation: without diverse voices in decision-making, policies fail to reflect lived experiences.

- Unequal access to support: marginalised staff often struggle to access resources like legal aid or peer advocacy, skewing outcomes.

Without intentional intervention, this power imbalance reinforces harm and excludes key voices.

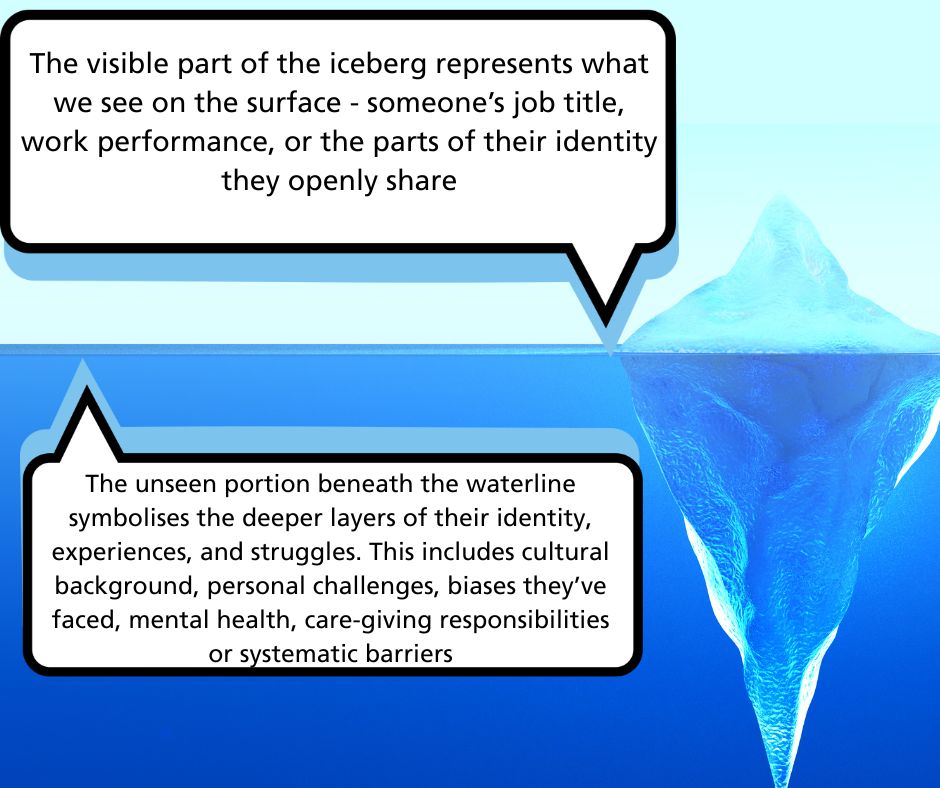

The iceberg model: what’s beneath the surface?

The iceberg model of identity reminds us that while job roles and professional conduct are visible, hidden factors—cultural background, personal challenges, systemic barriers—significantly impact investigations.

personal challenges, systemic barriers—significantly impact investigations.

For instance, international NHS staff, especially nurses, may experience language barriers, family separation, or housing difficulties, yet these factors are rarely considered. A compassionate, culturally aware approach is crucial to fair investigations.

Breaking bias: understanding cultural lenses

One of the most eye-opening lessons from our training was how our own cultural perspectives shape our judgments. Unconsciously, we apply assumptions based on our personal norms, failing to consider the diversity of perspectives.

To challenge this, we must:

🔹 Question our biases when reviewing cases.

🔹 Encourage diverse decision-making panels.

🔹 Acknowledge intersectionality in investigations.

A shared responsibility for change

Intersectionality isn’t just the responsibility of marginalised individuals—it’s a collective commitment. Workplace training often focuses on single identity groups (e.g., leadership programmes for women or neurodiverse individuals), but what about ethnically diverse women with neurodiversity in leadership?

A holistic, inclusive approach is needed - one that embraces multiple identity layers rather than treating them in isolation. The conversation starts here, but the work must continue. Let’s commit to real, lasting change.